It is also a country that is divided into regions and most of Southeast Asia's longest river, the largest flower in the world, and the largest butterfly in the world. The largest cave in the world's oldest tropical rainforest, and the first person appeared in southeast Asia can be found in Sarawak. Sarawak has shown unique and distinctive.

Tourist areas in Sarawak consists of natural areas and cultural centers such as the Sarawak Cultural Village. Natural areas that are popular among tourists as well as Overseas located in the Kuching include Wind Cave and Cave of Pari, Ranchan Park, Wildlife Park Matang and Semenggoh Orang Utan Conservation Center.

Dayak People;

Dayak the native people of Borneo. It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic subgroups, located principally in the interior of Borneo, each with its own dialect, customs, laws, territory and culture, although common distinguishing traits are readily identifiable. Dayak languages are categorized as part of the Austronesian languages in Asia. The Dayak were animist in belief; however many converted to Christianity, and some to Islam more recently. Estimates for the Dayak population range from 18 to 20 million. Dayak people are divided into some sub-ethnics that have different language and even different way of living. Shortly, Dayak is referred to Ngaju People or Ot Danum tribe who stays in South Borneo. While, in general, Dayak is referred to the 6 tribes of Dayak; [Kenyah-Kayan-Bahau],[Ot Danum],[Iban],[Murut],[Kalimantan] and [Punan]. Those six clusters were subdivided into approximately 405 sub-clusters. Although divided into hundreds of sub-clusters, Dayak groups have similar cultural traits in particular ways. These characteristics become the deciding factor if a sub-tribe in Borneo which can be incorporated into the group of Dayak.

Dates back to the history, in the year 1977-1978, the Asian continent and the island of Borneo, which is part of the archipelago are still together, allowing the Mongoloid races of the Asian mainland to wander through and up through the mountains of Borneo to the mountains which is now called “Muller-Schwaner mountain. Dayak people was true the Borneo indigenous. However, after the Malays from Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula came, they increasingly retreated back inside. Moreovheer, arrival of the Bugis, Makasar, and the Javanese in time of Majapahit Empire. Dayak people was living scattered throughout the territory of Kalimantan in the span of time, they have spread through the rivers to downstream and then inhabit the coast of Borneo island.

It was analyzed that Dayak people had to build an empire. In the oral tradition of Dayaks, often called “Nansarunai Uak Jawa” which means, A kingdom of Dayak Nansarunai was destroyed by Majapahit. This was occurring between the years 1309-1389. The incident resulted the Dayaks get insurgency and dispersed, some of them was get into the hinterland. The next big flows occur when the influenced of Islam that originated from the kingdom of Dayak, with the influx of traders Melayu around 1608.

In the past the Dayak people were the tribe who practicing the ancient tradition of headhunting. After conversion to Islam or Christianity and anti-headhunting legislation by the colonial powers, the practice was banned and disappeared. Nevertheless, some said that Dayak people practicing cannibalism only when the war is occur and their life is in danger. In other word, practicing cannibalism is not the term of the way of living or part of the culture, but it is just the consequences that Dayak people have for someone’s disturbance within their groups.

Dayak people have various types of weapons which commonly used for hunting and war in ancient time, or for everyday use such as in the fields. For example blowpipe (sipet), saber, lonjo (spear), shield (telawang), and spurs. Originally, the main icon from Dayak weapon is Sumpitan, not Mandau. Mandau was being used to cut the enemies head in ancient time, when the war was occur. While sumpitan is still exist until present time, and there is no antidote from the poison in sumpitan. Sumpitan is such a bamboo wooden stick along the 1.9 meters to 2.1 meters. Sumpitan should be made of hard wood such as ironwood, tampang, lanan, berangbungkan, rasak, or plepek wood.

More about Dayak people, they also use tattoo in their culture. Tattoo for Dayak people is referred to religion, social status in society, as well as the appreciation for a person. Therefore, the tattoo cannot be made arbitrarily. There are certain rules in making a tattoo or Parung, good selection of pictures, the social structure of the tattooed and the tattoo placement. The belief that the meaning of making tattoo is used to be a torch when the death occurs. The more they have tattoo, the more they are lighten when they die. Still, making a tattoo cannot be made as much in vain, because it must comply with customs rules.

The main religion of Dayak people in ancient time was Kaharingan, such as animism but similar to Hindu in present time. Over the last two centuries, some Dayaks converted to Islam, abandoning certain cultural rites and practices. Christianity was introduced by European missionaries in Borneo. Religious differences between Muslim and Christian natives of Borneo has led, at various times, to communal tensions.

For everyday living, Dayak people nowadays are depended their life in agricultural things like planting the rice field, planting bananas or palm oil. Following the modernity that came up nowadays, Dayak people are more to be a modern society, bust still hold the heritage to be the real Dayak.

History;

The main ethnic groups of Dayaks are the Bakumpai and Dayak Bukit of South Kalimantan, The Ngajus, Baritos, Benuaqs of East Kalimantan, the Kayan and Kenyah groups and their sub-tribes in Central Borneo and the Ibans, Embaloh (Maloh), Kayan, Kenyah, Penan, Kelabit, Lun Bawang and Taman populations in the Kapuas and Sarawak regions. Other populations include the Ahe, Jagoi, Selakau, Bidayuh, and Kutai.

The Dayak people of Borneo possess an indigenous account of their history, partly in writing in papan turai (wooden records), partly in common cultural customary practices and partly in oral literature. In addition, colonial accounts and reports of Dayak activity in Borneo detail carefully-cultivated economic and political relationships with other communities as well as an ample body of research and study considering historical Dayak migrations. In particular, the Iban or the Sea Dayak exploits in the South China Seas are documented, owing to their ferocity and aggressive culture of war against sea dwelling groups and emerging Western trade interests in the 19th and 20th centuries.

In 1838 James Brooke, a British adventurer with an inheritance and an armed sloop arrived to find the Brunei Sultanate fending off rebellion from war like inland tribes. Sarawak was in chaos, Brooke put down the rebellion and as a reward signed a treaty in 1841 was bestowed the title Governor and granted power over parts of Sarawak. He pacified the natives, suppressed headhunting, eliminated the much-feared Borneo pirates, bringing ever growing tracts of Borneo under their control. In Sarawak, the most famous Iban enemy of the Brooke was Libau “Rentap” who was only defeated at Sadok Hill after three expeditions by the Brooke who was helped by some Dayaks themselves and thus, the Brooke famously said “Only Dayaks can kill Dayaks”. Shariff Mashor was another enemy to the Brooke who was a Melanau from Mukah.

During World War II, the Japanese occupied Borneo and treated all of the indigenous peoples poorly – massacres of the Malay and Dayak peoples were common, especially among the Dayaks of the Kapit Division. Following this treatment, the Dayaks formed a special force to assist the Allied forces. Eleven United States airmen and a few dozen Australian special operatives trained a thousand Dayaks from the Kapit Division to battle the Japanese with guerrilla warfare. This army of tribesmen killed or captured some 1,500 Japanese soldiers and were able to provide the Allies with intelligence vital in securing Japanese-held oil fields.

Coastal populations in Borneo are largely Muslim in belief, however these groups (Tidung, Bulungan, Paser, Melanau, Kadayan, Bakumpai, Bisayah) are generally considered to be Islamized Dayaks, native to Borneo, and heavily influenced by the Javanese Majapahit Kingdoms and Islamic Malay Sultanates.

Other groups in coastal areas of Sabah, Sarawak and northern Kalimantan; namely the Illanun, Tausug, Sama and Bajau, although inhabiting and (in the case of the Tausug group) ruling, the northern tip of Borneo for centuries, have their origins from the southern Philippines. These groups are not Dayak, but instead are grouped under the separate umbrella term of Moro.

Etymology;

The term ” Dayak ” most commonly used to refer to the native non – Muslim , non – Malay who live on the island. This is especially true in Malaysia , because in Indonesia there Dayak tribes are Muslim but still Dayak category although some of them referred to the tribe Banjar and Kutai tribe . There are various explanations about the etymology of this term. According to Lindblad , Dayak word is derived from the power of the Kenyah language , which means upstream or inland . King , further speculate that the Dayak may also be derived from the word “aja” , a Malay word meaning native or indigenous . He also believes that the word is probably derived from a term of Central Java language that means behavior that is not appropriate or is not in place.

The term for the native tribes near Sambas and Pontianak is Power ( Kanayatn : the power = the landline ) , whereas in Banjarmasin called Biaju ( bi = from ; aju = upstream ). Thus the original term Power ( the landline ) intended to native of West Kalimantan which clumps hereinafter called Dayak Bidayuh Land Dayak are distinguished by the Sea ( clumps Iban ) . In Banjarmasin , the term Dayak started to be used in agreement with the Sultan of Banjar Dutch East Indies in 1826 , to replace the term Biaju Large ( Kahayan river area ) and Small Biaju ( Moody Kapuas river region ) , each of which was changed to Dayak Dayak Large and Small . Since then the term Dayak is also intended to Ngaju – Ot Danum clump or clumps Barito . Furthermore, the term ” Dayak ” is used to refer collectively extends to the native tribes of different local languages, especially the non – Malays or non- Muslims. At the end of the 19th century ( after the Peace tumbles Anoi ) term used in the context of population Dayak colonial rulers who took over the sovereignty of the tribes living in the hinterlands of Borneo. According to the Ministry of Education and Culture Project Assessment and Development Section Cultural Values in East Kalimantan , Dr . Kaderland August , a Dutch scientist , was the first person to use the term Dayak in the definition above in 1895 .

The meaning of the word ‘ Dayak ‘ itself is debatable . Commans ( 1987) , for example , writes that according to some authors , ‘ Dayak ‘ means man , while other authors stated that the word means inland . Commans said that the most proper sense is people living in the river upstream. In a similar name , Lahajir et al reported that people use the term Dayak Iban with a human sense , while people Benuaq Alas and interpret it as upstream. They also stated that some people claim that the term Dayak refers to certain personal characteristics that are recognized by the people of Borneo , which is strong , manly , brave and tenacious . Lahajir et al noted that there are at least four terms to the original penuduk Borneo in the literature , namely Power ‘ , Dyak , Power , and Dayak . The natives themselves are generally not familiar with these terms , but the people outside of the scope they are referred to them as ‘ Dayak ‘.

Sub-Ethnic Division;

Due to the strong migration of settlers, who still retain Dayak indigenous culture ultimately chose to go into the interior. As a result, the Dayak became scattered and become its own sub-sub-ethnic. Dayak groups, divided into sub-sub-tribe numbers approximately 405 sub (by JU Lontaan, 1975). Each sub tribe Dayak in Borneo have customs and cultures are similar, refer to the sociology of community service and differences in customs, culture, or language typical. Past society now called Dayak, inhabit coastal areas and rivers in each of their settlements. Dayaks of Borneo by an anthropology JU Lontaan, 1975 in book Customary Law and Customs of West Kalimantan, consisting of six major tribes and 405 sub-tribes are small, which is spread across Borneo.

Origin;

In general, most people in the archipelago is the speakers. Currently the dominant theory is proposed linguists such as Peter Bellwood and Blust , namely that the place of origin is Taiwan’s Austronesian languages . Around 4000 years ago , a group of Austronesian people began migrating to the Philippines . Approximately 500 years later, no group has begun to migrate south to the islands of Indonesia now , and to the east towards the Pacific .

But this is not the Austronesian sourdough Borneo island . Between 60 000 and 70 000 years ago , when sea levels 120 or 150 meters lower than today and the Indonesian island of land ( geologists call this land ” Sunda ” ) , humans had migrated from Asia to the south and had reached the Australian continent who was not too far away from mainland Asia .

From the mountains that come across the great rivers of Borneo. It is estimated that, in the long span of time , they have to spread tracing rivers to downstream and then inhabit the coast of the island of Borneo. It turned Tahtum tells migration of local Dayak Ngaju perhuluan rivers heading downstream rivers .

In the southern area of the Dayak Kalimantan never build an empire. In the oral tradition of the Dayak in the area often referred to Usak Nansarunai Java, namely the kingdom of Dayak Maanyan Nansarunai destroyed by the Majapahit , which is expected to occur between the years 1309 to 1389. The incident resulted Dayak Maanyan urgency and scattered, partly into the hinterland to the area of the Dayak tribe Lawangan . The next big flow occurs during the Islamic influence came from the kingdom of Demak with the entry of Malay traders (circa 1520 ).

Most of the Dayak tribes in the south and east Kalimantan who embraced Islam out of the Dayak tribe and no longer recognizes him as the Dayaks , but refer to themselves as a tribe or people of Banjar and Kutai . While the Dayak people who reject Islam back down the river , into the interior , live in areas of Tangi Wood , Amuntai , Margasari , Watang Amandit , Labuan Amas and Watang Balangan . Some are kept pressed for entering the jungle . Muslims Dayaks are mostly located in the South and most Kotawaringin , one of the leaders of the famous Hindu Banjar is Gastric Mangkurat according to Dayak is a Dayak ( Ma’anyan or Ot Danum ). In East Kalimantan , the Tribe Tonyoy – Benuaq who embraced Islam calls itself a tribe Kutai. Not only of the archipelago, other nations also came to Borneo . Chinese people began to come to Kalimantan recorded during the Ming dynasty recorded in Book 323 History of the Ming Dynasty ( 1368-1643 ) . Hanzi lettered manuscript mentioned that the city was first visited Banjarmasin and mentioned that a bloody Prince Sultan Hidayatullah Biaju be a substitute for the first. The visit at the time of Sultan Hidayatullah I and his successor, Sultan Mustain Billah . Hikayat Banjar preach visit but not settled by Chinese traders and European nations jung ( called Walanda ) in South Kalimantan has occurred in the Hindu kingdom of Banjar ( XIV century ). Chinese merchants began to settle in the city of Banjarmasin at a place near the beach in 1736.

The arrival of the Chinese in southern Borneo Dayak population does not lead to the displacement and does not have a direct effect because they only trade , especially with the kingdom of Banjar Banjarmasin . They do not directly trade with the Dayaks . Remains of the Chinese nation was saved by some Dayak tribes like malawen plates, pots ( jars ) and ceramic equipment .

Since the beginning of the fifth century the Chinese nation has reached Borneo. In the fifteenth century Yongle Emperor sent a large army to the south ( including the archipelago ) under the leadership of Zheng He , and returned to China in 1407 , having previously stopped to Java , Borneo , Malacca , Manila and Solok . In 1750, Sultan Mempawah accept Chinese people (from Brunei) who were looking for gold . Chinese people are also carrying merchandise including opium, silk, glassware such as plates , cups , bowls and jars.

Agriculture;

Traditionally, Dayak agriculture was based on widen rice cultivation. Agricultural Land in this sense was used and defined primarily in terms of hill rice farming, ladang (garden), and hutan (forest). Dayaks organized their labour in terms of traditionally based land holding groups which determined who owned rights to land and how it was to be used. The “green revolution” in the 1950s, spurred on the planting of new varieties of wetland rice amongst Dayak tribes.

The main dependence on subsistence and mid-scale agriculture by the Dayak has made this group active in this industry. The modern day rise in large scale monocarp plantations such as palm oil and bananas, proposed for vast swathes of Dayak land held under customary rights, titles and claims in Indonesia, threaten the local political landscape in various regions in Borneo.

Further problems continue to arise in part due to the shaping of the modern Malaysian and Indonesian nation-states on post-colonial political systems and laws on land tenure. The conflict between the state and the Dayak natives on land laws and native customary rights will continue as long as the colonial model on land tenure is used against local customary law. The main precept of land use, in local customary law, is that cultivated land is owned and held in right by the native owners, and the concept of land ownership flows out of this central belief. This understanding of custom is based on the idea that land is used and held under native domain. Invariably, when colonial rule was first felt in the Kalimantan Kingdoms, conflict over the subjugation of territory erupted several times between the Dayaks and the respective authorities.

Religion;

The Dayak indigenous religion has been given the name Kaharingan, and may be said to be a form of animism. For official purposes, it is categorized as a form of Christian in Indonesia. Nevertheless, these generalizations fail to convey the distinctiveness, meaningfulness, richness and depth of Dayak religion, myth and teachings.

Underlying the world-view is an account of the creation and re-creation of this middle-earth where the Dayak dwell, arising out of a cosmic battle in the beginning of time between a primal couple, a male and female bird/dragon (serpent). Representations of this primal couple are amongst the most pervasive motifs of Dayak art. The primal mythic conflict ended in a mutual, procreative murder, from the body parts of which the present universe arose stage by stage. This primal sacrificial creation of the universe in all its levels is the paradigm for, and is re-experienced and ultimately harmoniously brought together (according to Dayak beliefs) in the seasons of the year, the interdependence of river (up-stream and down-stream) and land, the tilling of the earth and fall of the rain, the union of male and female, the distinctions between and cooperation of social classes, the wars and trade with foreigners, indeed in all aspects of life, even including tattoos on the body, the lay-out of dwellings and the annual cycle of renewal ceremonies, funeral rites, etc.

The Iban Dayak religion can be simply referred to as the Iban religion which has been written by Benedict Sandin and others extensively. It is characterized by a supreme being in the name of Bunsu (Kree) Petara who has no parents and creates everything in this world and other worlds. Under Bunsu Petara are the seven gods whose names are: Sengalang Burong as the god of war and healing, Biku Bunsu Petara as the high priest and second in command, Menjaya as the first shaman (manang) and god of medicine, Selampandai as the god of creation, Sempulang Gana as the god of agriculture and land along with Semarugah, Ini Inda/Inee/Andan as the naturally-born doctor and god of justice and Anda Mara as the god of wealth.

The praying and propitiation to certain gods are held via four main categories of rituals and festivals (gawai). The first category is the agricultural-related festivals which are dedicated to paddy farming to honour Sempulang Gana and include Gawai Batu (Whetstone Festival), Gawai Ngalihka Tanah (Soil Reactivation Festival), Gawai Benih (Padi Seed Festival), Gawai Ngemali Umai (Farm Curing Festival), Gawai Matah (Harvest Initiation Festival) and Gawai Bersimpan (Paddy Storing Festival). The second category is the headhunting-related festivals to honour Sengalang Burong comprises Gawai Burung (Bird Festival) and Gawai Kenyalang (Hornbill Festival) which are held after other smaller rituals like bedara matak (first offering inside the family room), bedara mansau (second-in-scale offering inside the family room), sandau ari (mid-day celebration) and enchaboh arong (head-welcoming ceremony) are performed. The third category is the sickness-healing festivals to ask for curing from Menjaya or Ini Andan such as Gawai Sakit (Sickness Festival) which is held after other smaller attempts have failed to cure the sicked persons such as begama (touching), belian (various manang rituals), Besugi Sakit (to ask Keling for curing via magical power) and Berenong Sakit (to ask for curing by Sengalang Burong) in the ascending order. Gawai Burung can also be used for healing certain difficult-to-cure sickness via magical power by Sengalang Burong especially nowadays after headhunting has been stopped. Two more festivals that are related to wellness and longevity are Gawai Betambah Bulu (Hair Adding Festival) and Gawai Nanga Langit (Sky Staircasing Festival). The fourth category is the fortune-related festivals which consist of Gawai Pangkong Tiang (Post Banging Festival) after trasfering to a new longhouse, Gawai Tuah (Luck Festival) with three ascending stages to seek and to welcome lucks and Gawai Tajau (Jar Festival) to welcome newly acquired jars. The fifth category is the Soul Festival (Gawai Antu) for the souls of the deads. The seven and last category is the Gawai Mimpi (Dream Festival) which is held for any dreams experienced during sleep where good meaning dreams are purposely sought.

At the end of these festivals except Gawai Antu, the divination of the pig liver will be interpreted to forecast the outcome of the future or the luck of the individual who holds the festival.

The Iban Dayaks have several methods to receive omens where good omens are purposely sought. The first method is via dream to receive charms, amulets (pengaroh, empelias. engkerabun) or medicine (obat) and curse (sumpah) from any gods, people of Panggau Libau and Gelong and any spirits or ghosts. The second method is via animal omens (burong laba) which have long lasting effects such as from deer barking which is quite random in nature. The third method is via bird omens (burong bisa) which have short term effects that are commonly limited to a certain farming year or a certain activity at hands. The forth method is via pig liver divination after festival celebration The fifth but not the least method is via nampok or betapa (self-imposed isolation) to receive amulet, curse, medicine or healing.

There are seven omen birds under the charge of their chief Sengalang Burong at their longhouse named Tansang Kenyalang (Hornbill Abode), which are Ketupong (Jaloh or Kikeh) (Rufous Piculet) as the first in command, Beragai (Scarlet-rumped trogon), Pangkas (Maroon Woodpecker) on the righthand side of Sengalang Burong’s family room while Bejampong as the second in command, Embuas (Banded Kingfisher), Kelabu Papau (Senabong) (Diard’s Trogon) and Nendak (White-rumped shama) on the lefthand side. The calls and flights of the omen birds along with the circumstances and social status of the listeners are considered during the omen interpretations.

The prayers to gods and/or other spirits are made by giving offerings (“piring”) and animal sacrifices (“genselan”). The number (leka or turun) of each piring offering item is based on ascending odd numbers which have meanings and purposes as below:

piring 3 for piring ampun (forgiveness seeking) or seluwak (wastefulness spirit)

piring 5 for piring minta (reguest offering) or bejalai (journey)

piring 7 for piring begawai (festival) or bujang berani (brave warrior)

piring 9 for sangkong (including others) or turu (leftover included)

Piring contains offering of various traditional foods and drinks while genselan is made by sacrificing chickens and/or pigs. Bedara is commonly held for any general purposes before holding any festivals.

Any Iban Dayak will undergo some forms of simple rituals and several elaborate festivals as necessary in their lifetime from a baby, adolescent to adulthood. The longhouse where the Iban Dayaks stay is constructed in a unique way for both living or accommodation purposes and ritual or religious practices.

The shaman (manang) of the Iban Dayaks have various types of pelian (ritual healing ceremony) to be held in accordance with the types of sickness determined by him through his glassy stone to see the whereabouts of the soul of the sick person.

Over the last two centuries, some Dayaks converted to Christianity and Islam, abandoning certain cultural rites and practices. Christianity was introduced by European missionaries in Borneo. Religious differences between Muslim and Christian natives of Borneo has led, at various times, to communal tensions. Relations, however between all religious groups are generally good.

Muslim Dayaks have however retained their original identity and kept various customary practices consistent with their religion. However many Christian Dayak has changed their name to European or English name but some minority still maintain their ancestors traditional name.

An example of common identity, over and above religious belief, is the Melanau group. Despite the small population, to the casual observer, the coastal dwelling Melanau of Sarawak, generally do not identify with one religion, as a number of them have Islamized and Christianised over a period of time. A few practise a distinct Dayak form of Kaharingan, known as Liko. Liko is the earliest surviving form of religious belief for the Melanau, predating the arrival of Islam and Christianity to Sarawak. The somewhat patchy religious divisions remain, however the common identity of the Melanau is held politically and socially. Social cohesion amongst the Melanau, despite religious differences, is markedly tight within their small community.

Despite the destruction of pagan religions in Europe by Christians, most of the people who try to conserve the Dayaks’ religion are missionaries. For example Reverend William Howell contributed numerous articles on the Iban language, lore and culture between 1909-1910 to the Sarawak Gazette. The articles were later compiled in a book in 1963 entitled, The Sea Dayaks and Other Races of Sarawak.

Society;

Kinship in Dayak society is traced in both lines of genealogy (tusut). Although, in Dayak Iban society, men and women possess equal rights in status and property ownership, political office has strictly been the occupation of the traditional Iban patriarch. There is a council of elders in each longhouse.

Overall, Dayak leadership in any given region, is marked by titles, a Penghulu for instance would have invested authority on behalf of a network of Tuai Rumah’s and so on to a Pemancha, Pengarah to Temenggung in the ascending order while Panglima or Orang Kaya (Rekaya) are tittles given by Malays to some Dayaks.

Individual Dayak groups have their social and hierarchy systems defined internally, and these differ widely from Ibans to Ngajus and Benuaqs to Kayans.

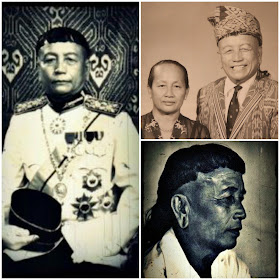

In Sarawak, Temenggong Koh Anak Jubang was the first paramount chief of Dayaks in Sarawak and followed by Tun Temenggong Jugah Anak Barieng who was one of the main signatories for the formation of Federation of Malaysia between Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak with Singapore expelled later on. He was said to be the “bridge between Malaya and East Malaysia”. The latter was fondly called “Apai” by others, which means father. Unfortunately, he had no western or formal education at all.

The most salient feature of Dayak social organisation is the practice of Longhouse domicile. This is a structure supported by hardwood posts that can be hundreds of metres long, usually located along a terraced river bank. At one side is a long communal platform, from which the individual households can be reached.

The Iban of the Kapuas and Sarawak have organized their Longhouse settlements in response to their migratory patterns. Iban longhouses vary in size, from those slightly over 100 metres in length to large settlements over 500 metres in length. Longhouses have a door and apartment for every family living in the longhouse. For example, a longhouse of 200 doors is equivalent to a settlement of 200 families.

The tuai rumah (long house chief) can be aided by a tuai burong (bird leader), tuai umai (farming leader) and a manang (shaman). Nowadays, each long house will have a Security and Development Committee and ad hoc committee will be formed as and when necessary for example during festivals such as Gawai Dayak.

The Dayaks are peace loving people who live based on customary rules or adat asal which govern each of their main activities. The adat is administered by the tuai rumah aided by the Council of Elders in the longhouse so that any dispute can be settled amicably among the dwellers themselves via berandau (discussion). If no settlement can be reached at the longhouse chief level, then the dispute will escalate to a pengulu level and so on.

Adat berumah (House building rule)

Adat melah pinang, butang ngau sarak (Marriage, adultery and divorce rule)

Adat beranak (Child bearing and raising rule)

Adat bumai and beguna tanah (Agricultural and land use rule)

Adat ngayau (Headhunting rule)

Adat ngasu, berikan, ngembuah and napang (Hunting, fishing, fruit and honey collection rule)

Adat tebalu, ngetas ulit ngau beserarak bungai(Widow/widower, mourning and soul separation rule)

Adat begawai (festival rule)

Adat idup di rumah panjai (Order of life in the longhouse rule)

Adat betenun, main lama, kajat ngau taboh (Weaving, past times, dance and music rule)

Adat beburong, bemimpi ngau becenaga ati babi (Bird and animal omen, dream and pig liver rule)

Adat belelang (Journey rule).

The Dayak life centres on the paddy planting activity every year. The Iban Dayak has their own yearlong calendar with 12 consecutive months which are one month later than the Roman calender. The months are named in accordance to the paddy farming activities and the activities in between. Other than paddy, also planted in the farm are vegetables like ensabi, pumpkin, round brinjal, cucumber, corn, lingkau and other food sources lik tapioca, sugarcane, sweet potatoes and finally after the paddy has been harvested, cotton is planted which takes about two months to complete its cycle. The cotton is used for weaving before commercial cotton is traded. Fresh lands cleared by each Dayak family will belong to that family and the longhouse community can also use the land with permission from the owning family. Usually, in one riverine system, a special track of land is reserved for the use by the community itself to get natural supplies of wood, rattan and other wild plants which are necessary for building houses, boats, coffins and other living purposes, and also to leave living space for wild animals which is a source of meat. Beside farming, Dayaks plant fruit trees like rambutan, langsat, durian, isu and mangosteen near their longhouse or on their land plots to amrk their ownership of the land. They also grow plants which produce dyes for colouring their cotton treads if not taken from the wild forest. Major fishing using the tuba root is normally done by the whole longhouse as the river may take sometimes to recover. Any wild meat obtained will distribute according to a certain customary law.

Headhunting was an important part of Dayak culture, in particular to the Iban and Kenyah. The origin of headhunting in Iban Dayaks can be traced to the story of a chief name Serapoh who was asked by a spirit to obtain a fresh head to open a mourning jar but unfortunately he killed a Kantu boy which he got by exchanging with a jar for this purpose for which the Kantu retaliated and thus starting the headhunting practice.[13] There used to be a tradition of retaliation for old headhunts, which kept the practice alive. External interference by the reign of the Brooke Rajahs in Sarawak via “bebanchak babi” (peacemaking) in Kapit and the Dutch in Kalimantan Borneo via peacemaking at Tumbang Anoi curtailed and limited this tradition.

Apart from massed raids, the practice of headhunting was then limited to individual retaliation attacks or the result of chance encounters. Early Brooke Government reports describe Dayak Iban and Kenyah War parties with captured enemy heads. At various times, there have been massive coordinated raids in the interior and throughout coastal Borneo before and after the arrival of the Raj during Brooke’s reign in Sarawak.

The Ibans’ journey along the coastal regions using a large boat called “bandong” with sail made of leaves or cloths may have given rise to the term, Sea Dayak, although, throughout the 19th Century, Sarawak Government raids and independent expeditions appeared to have been carried out as far as Brunei, Mindanao, East coast Malaya, Jawa and Celebes.

Tandem diplomatic relations between the Sarawak Government (Brooke Rajah) and Britain (East India Company and the Royal Navy) acted as a pivot and a deterrence to the former territorial ambitions, against the Dutch administration in the Kalimantan regions and client sultanates.

In the Indonesian region, toplessness was the norm among the Dayak people, Javanese, and the Balinese people of Indonesia before the introduction of Islam and contact with Western cultures. In Javanese and Balinese societies, women worked or rested comfortably topless. Among the Dayak, only big breasted women or married women with sagging breasts cover their breasts because they interfered with their work. Once marik empang (top cover over the shoulders) and later shirts are available, toplessness has been abandoned.

Metal-working is elaborately developed in making mandaus (machetes – parang in Malay and Indonesian). The blade is made of a softer iron, to prevent breakage, with a narrow strip of a harder iron wedged into a slot in the cutting edge for sharpness in a process called ngamboh (iron-smithing).

In headhunting it was necessary to able to draw the parang quickly. For this purpose, the mandau is fairly short, which also better serves the purpose of trailcutting in dense forest. It is holstered with the cutting edge facing upwards and at that side there is an upward protrusion on the handle, so it can be drawn very quickly with the side of the hand without having to reach over and grasp the handle first. The hand can then grasp the handle while it is being drawn. The combination of these three factors (short, cutting edge up and protrusion) makes for an extremely fast drawing-action.

The ceremonial mandaus used for dances are as beautifully adorned with feathers, as are the costumes. There are various terms to describe different types of Dayak blades. The Nyabor is the traditional Iban Scimitar, Parang Ilang is common to Kayan and Kenyah Swordsmiths, pedang is a sword with a metallic handle and Duku is a multipurpose farm tool and machete of sorts.

Normally, the sword is accompanied by a wooden shield called terabai which is decorated with a demon face to scare off the enemy. Another weapons are sangkoh (spear) and sumpit (blowpipe) with lethal poison at the tip of its laja. To protect the upper body during combat, a gagong (armour) which is made of animal hard skin such as leopards is worn over the shoulders via a hole made for the head to enter.

Dayaks normally build their longhouses on high posts on high ground where possible for protection. They also may build kuta (fencing) and kubau (fort) where necessary to defend against enemy attacks. Dayaks also possess some brass and cast iron weaponry such as brass cannon (bedil) and iron cast cannon meriam. Furthermore, Dayaks are experienced in setting up animal traps (peti) which can be used for attacking enemy as well. The agility and stamina of Dayaks in jungles give them advantages. However, at the end, Dayaks were defeated by handguns and disunity among themselves against the colonialists.

Most importantly, Dayaks will seek divine helps to grant them protection in the forms of good dreams or curses by spirits, charms such as pengaroh (normally ponsonous), empelias (weapon straying away) and engkerabun (hidden from normal human eyes), animal omens, bird omens, good divination in the pig liver or by purposely seeking supernatural powers via nampok or betapa or menuntut ilmu (learning knowledge) especially kebal (weapon-proof).[39] During headhunting days, those going to farms will be protected by warriors themselves and big agriculture is also carried out via labour exchange called bedurok (which means a large number of people working together) until completion of the agricultural activity. Kalingai or pantang (tattoo) is made unto bodies to protect from dangers and other signifying purposes such as traveling to certain places.

The traditional Iban Dayak male attire consists of a sirat (loincloth) attached with a small mat for sitting), lelanjang (headgear with colourful bird feathers) or a turban (a long piece of cloth wrapped around the head), marik (chain) around the neck, engkerimok (ring on thigh) and simpai (ring on the upper arms). The Iban Dayak female traditional attire comprises a short “kain tenun betating” (a woven cloth attached with coins and bells at the bottom end), a rattan or brass ring corset, selampai (long scarf) or marik empang (beaded top cover), sugu tinggi (high comb made of silver), simpai (bracelets on upper arms), tumpa (bracelets on lower arms) and buah pauh (fruits on hand).

The Dayaks especially Ibans appreciate and treasure very much the value of pua kumbu (woven or tied cloth) made by women while ceramic jars which they call tajau obtained by men. Pua kumbu has various motives for which some are considered sacred. Tajau has various types with respective monetary values. The jar is a sign of good fortune and wealth. It can also be used to pay fines if some adat is broken in lieu of money which is hard to have in the old days. Beside the jar being used to contain rice or water, it is also used in ritual ceremonies or festivals and given as baya (provision) to the dead.

The adat tebalu (widow or widower fee) for deceased women for Iban Dayaks will be paid according to her social standing and weaving skills and for the men according to his achievements in lifetime.

Dayaks being accustomed to living in jungles and hard terrains, and knowing the plants and animals are extremely good at following animals trails while hunting and of course tracking humans or enemies, thus some Dayaks became very good trackers in jungles in the military e.g. some Iban Dayaks were engaged as trackers during the anti-confrontation by Indonesia against the formation of Federation of Malaysia and anti-communism in Malaysia itself. No doubt, these survival skills are obtained while doing activities in the jungles, which are then utilized for headhunting in the old days.

Dayak People In The Present.

Today Dayak tribes are divided into six large clumps , namely : Apokayan ( Kenyah – Kayan – Bahau ) , Ot Danum – Ngaju , Iban , Murut , Klemantan and Punan . Clumps Dayak Dayak Punan is the oldest inhabited the island of Borneo , Dayak clumps while others are the result of assimilation between the clumps and Punan Dayak groups Proto Malay ( Dayak ancestors who came from Yunnan ) . Sixth clump was subdivided into approximately 405 sub – ethnic . Although divided into hundreds of sub – ethnic , all have in common Dayak ethnic cultural traits typical . These characteristics be the deciding factor whether a subsuku in Borneo can be incorporated into the Dayak groups or not . These characteristics are the length , the results of material culture such as pottery , saber , chopsticks , beliong ( ax Dayak ) , views on nature , livelihood ( farming system ) , and the art of dance . Ot Danum Dayak village clump – Ngaju usually called Lewu / dust and the other Dayak often referred banua / continent / binua / benuo . In sub-districts in Kalimantan, which is an area of the Dayak Customary led by a Chief who led one or two different Dayak tribes .

Prof . Lambut from the University of Hull Mangkurat , ( Ngaju Dayak ) rejected the notion derived from the Dayak tribe of origin , but only the collective designation of various ethnic elements , according to him are ” racial ” , the Dayak people can be grouped into :

Dayak Mongoloid

Malayunoid

Autrolo – Melanosoid

Dayak Heteronoid

However, in the international scientific world , terms like ” race Australoid ” , ” Mongoloid races and in general ” race ” is no longer considered meaningful for classify human beings because of the complex factors that make the existence of human groups.

Dayak in Military;

Two highly decorated Iban Dayak soldiers from Sarawak in Malaysia are Temenggung Datuk Kanang anak Langkau (awarded Seri Pahlawan Gagah Perkasa) and Awang Anak Rawing of Skrang (awarded a George Cross). So far, only one Dayak has reached the rank of a general in the military that is Brigadier-General Stephen Mundaw in the Malaysian Army, who was promoted on 1 November 2010.

Malaysia’s most decorated war hero is Kanang Anak Langkau due to his military services helping to liberate Malaya (and later Malaysia) from the communists. Among all the heroes were 21 holders of Panglima Gagah Berani (PGB) which is the bravery medal with 16 survivors. Of the total, there are 14 Ibans, two Chinese army officers, one Bidayuh, one Kayan and one Malay. But the majorities in the Armed Forces are Malays, according to a book – Crimson Tide over Borneo. The youngest of the PGB holder is ASP Wilfred Gomez of the Police Force.

There were six holders of Sri Pahlawan (SP) Gagah Perkasa (the Gallantry Award) from Sarawak, and with the death of Kanang Anak Langkau, there is one SP holder in the person of Sgt. Ngalinuh (an Orang Ulu).

Politics;

Organised Dayak political representation in the Indonesian State first appeared during the Dutch administration, in the form of the Dayak Unity Party (Parti Persatuan Dayak) in the 30s and 40s. The feudal Sultanates of Kutai, Banjar and Pontianak figured prominently prior to the rise of the Dutch colonial rule.

Dayaks in Sarawak in this respect, compare very poorly with their organised brethren in the Indonesian side of Borneo, partly due to the personal fiefdom that was the Brooke Rajah dominion, and possibly to the pattern of their historical migrations from the Indonesian part to the then pristine Rajang Basin. Political circumstances aside, the Dayaks in the Indonesian side actively organised under various associations beginning with the Sarekat Dayak established in 1919, to the Parti Dayak in the 40s, and to the present day, where Dayaks occupy key positions in government.

In Sarawak, Dayak political activism had its roots in the SNAP (Sarawak National Party) and Pesaka during post-independence construction in the 1960s. These parties shaped to a certain extent Dayak politics in the State, although never enjoying the real privileges and benefits of Chief Ministerial power relative to its large electorate due to their own political disunity with some Dayaks joining various political parties instead of consolidating inside one single political party.

The first Sarawak chief minister was Datuk Stephen Kalong Ningkan who was removed as the chief minister in 1966 after court proceedings and amendments to both Sarawak state constitution and Malaysian federal constitution due to some disagreements with Malaya with regards to the 18-point Agreement as conditions for Malaysia Formation. Datuk Penghulu Tawi Sli was appointed as the second Sarawak chief minister who was a soft-spoken seat-warmer fellow and then replaced by Tuanku Abdul Rahman Ya’kub (a Melanau Muslim) as the third Sarawak chief minister in 1970 who in turn was succeeded by Abdul Taib Mahmud a (Melanau Muslim) in 1981 as fourth Sarawak chief minister.

Wave of Dayakism has surfaced at least twice among the Dayaks in Sarawak while they are on the opposition side of politics as follows:

SNAP won 18 seats (with 42.70% popular vote) out of total 48 seats in Sarawak state election, 1974 while the remaining 30 seats won by Sarawak National Front.

PBDS (Parti Bansa Dayak Sarawak), a breakaway of SNAP in Sarawak state election in 1987 won 15 seats while its partner Permas only won 5 seats. Overall, the Sarawak National Front won 28 constituencies with PBB 14; SUPP 11 and SNAP 3. In both cases, SNAP and PBDS (now both party are defunct) had joined the Malaysian National Front as the ruling coalition. Under Indonesia, Kalimantan is now divided into four self-autonomous provinces i.e. West, East, South and Middle Kalimantan.

Under Indonesia’s transmigration programme, settlers from densely populated Java and Madura were encouraged to settle in the Indonesian provinces of Borneo. The large scale transmigration projects initiated by the Dutch and continued following Indonesian independence, caused social strains.

During the killings of 1965-66 Dayaks killed up to 5,000 Chinese and forced survivors to flee to the coast and camps. Starvation killed thousands of Chinese children who were under eight years old. The Chinese refused to fight back, even though previously the Chinese had fought against the Dutch colonialist occupation of Indonesia, since they considered themselves “a guest on other people’s land” with the intention of trading only. 75,000 of the Chinese who survived were displaced, fleeing to camps where they were detained on coastal cities. The Dayak leaders were interested in cleansing the entire area of ethnic Chinese. In Pontianak, 25,000 Chinese living in dirty, filthy conditions were stranded. They had to take baths in mud. The massacres are considered a “dark chapter in recent Dayak history”.

In 2001 the Indonesian government ended the transmigration of Javanese settlement of Indonesian Borneo that began under Dutch rule in 1905.

From 1996 to 2003 there were violent attacks on Indonesian Madurese settlers, including executions of Madurese transmigrant communities. The violence included the Sampit conflict in 2001 in which more than 500 were killed in that year. Order was restored by the Indonesian Military.

Black Magic of Dayak;

1 . Boxing Nine Doors.. Your punch so strong.. one blow could be brutal..

2 . Heavy Earth spell.. Your body weight and finally made your bones can not support the weight of your body, all the bones broken, and eventually die.

3 . Eggplant arrows.. kind of witchcraft as in Java , we sent in the evening , for anyone who got .. our bodies become purple as eggplant , within 3 days surely die if not treated quickly .

4 . Arrow Lombok .. Some kind of black magic as well .. if exposed to our body and we feel the spiciness of red .. we will continue to thirst but always spiciness .. your body will become weak over time and within a maximum period of 1 week is definitely dead .

5 . Fur Perindu .. a kind of supernatural stuff .. in use to conquer the opposite sex that we want … if there is a sale … definitely FAKE ! ! ! as in the non-tradable .. This is taken from the unseen world .

6 . Oil Star .. occult oil in use to heal bone fractures .. within a week the bone will definitely connected .. any severe fracture ..

7 . Pig Necklace .. magical items taken when we fight against the demon pigs who live in the interior of Borneo jungle . useful for the thugs because we would be immune jab , bullets and threats of any sharp objects . but we will be exposed to the side effects can be cured without phlegm .

8 . Saber Demon .. This he has most macho .. can make enemies wherever they are .. to decide the target enemy ‘s head.

9 . Balm Evil .. Balm in taro in objects that are often used by our target.. in less than 4 days would have died with the diagnosis of a heart attack ..

Funeral rites of the dayak.

If the indigenous people of Bali have the grand ngaben cremation ceremony and the Toraja have elaborate funeral traditions, the Dayak Maanyan sub ethnic group who inhabit the Warukin Village, in Tabalong Regency, South Kalimantan also have extraordinary rituals to send the soul to the afterlife at its passing away.

The Dayak Maanyan inhabit the area that stretches across the border between the provinces of Central Kalimantan and South Kalimantan. According to customs and way of life, the Dayak Maanyan are divided into three branches. They are the Banua Lima, Paju Ampat, and Paju sepuluh. The Dayak Maanyan of Warukin Village in South Kalimantan belong to the Banua Lima branch that has certain (although not principal) differences with the other branches.

Although much of this community has been converted to Islam or Christianity from their original faith of ‘Kaharingan’, nevertheless, funeral rites are one of the ancient rituals that continue to be practiced today. The Dayak Maanyan believe that every person who passes away returns to his and her “original” homeland of perfection (a similar concept to heaven or nirvana). To reach this ultimate afterlife, a series of rituals must be conducted by their descendants and living relatives to ensure that the spirit will find the way to this ultimate state. These series of rituals are in a way a process to cleanse the soul of the deceased from any faults or sins that may prevent it from entering heaven, a purification of the soul for the afterlife.

The stages and variety of the Dayak Maanyan funeral rites are as follows:

1. Ijambe: The burning of the bones of the deceased. The rituals take ten days and night and are highlighted with the sacrificial slaughter of bulls, pigs, and chicken. Due to its high cost, this ceremony is usually conducted by large families or generations of descendants for their ancestors.

2. Ngadatun: A funeral ceremony reserved especially for those who died in a non-natural way (killed in battle) or for renowned figures or prominent leaders of society. The ceremony takes 7 days and nights.

3. Miya: A ritual ceremony at erecting the tomb for the deceased (membatur) and decorating the grave. In this ritual, food, clothing and other necessities are symbolically sent to the spirit of the deceased.

4. Bontang: The highest and most illustrious form of showing respect towards the deceased by the living family. This ceremony lasts 5 days and nights, when tens of pigs, hundreds of chicken, and also buffaloes are sacrificed .The essence of the ceremony is to send wealth and prosperity to the spirit of the deceased. The ritual is not a ritual of grief, but is more a festive ceremony.

5. Nuang Panuk: A membatur ceremony is a level lower than Miya, since it is only conducted for one night.

6. Siwah: The continuation of Miya which is conducted 40 days after Miya. The ritual is intended to call the spirit back to the family as a “Pangantu Pangantuhu”, to become friends and guardians of the family.

During these rituals, there is a unique process where in sacrificing a buffalo, the animal must first be speared before it is finally slaughtered. The ritual of spearing the buffalo is believed to express that a person must make great efforts or do strenuous work before one expect to can gain something, in a way symbolizing the process of life itself.

Burial traditions and ceremonies of death in Dayak tribes is set firmly in customary law . Burial systems vary in line with the long history of human arrival in Borneo. Historically there are three burial culture in Borneo:

burial without a container and without supplies , with the frame folded position .

burial in a stone coffin ( dolmen )

burial with container wood , bamboo , or woven mats . This is the final burial system develops.

No comments:

Post a Comment